So-called austerity, the stoic injunction, is the path towards universal destruction. It is the old, the fatal, competitive path. Pull in your belt is a slogan closely related to ‘gird up your loins,’ or the guns-butter metaphor.

So-called austerity, the stoic injunction, is the path towards universal destruction. It is the old, the fatal, competitive path. Pull in your belt is a slogan closely related to ‘gird up your loins,’ or the guns-butter metaphor.

– Wyndham Lewis

In the 2001 Planet of the Apes remake, the spacecraft that crash-landed thousands of years previously starts up on the first try. While this is useful to move a storyline forward, the real world seldom seems to work this way:

-

If you leave your car in the driveway for a year, and then expect it to start, you are likely to be disappointed.

-

If you do not go to the gym for a month, and expect your physical performance to match what you could do previously, you will hurt yourself.

-

If you are out of the workforce for 10 years – or 1 year – your work skills decline. More importantly, people who are involuntarily unemployed suffer from challenges of motivation and confidence, and employers value them less so finding new employment is more difficult. These people are certainly not Flourishing.

Flourishing requires activity. An inactive human cannot Flourish. And because this activity occurs in a wider economic ecosystem, high levels of Flourishing require high levels of economic metabolism.

So when we apply a little system thinking to the likely impact of universal austerity – that is, a decision to rapidly reduce the level of a major source of activity, government spending – a priori we would expect that the result would be a deterioration in economic system performance, a reduction in economic metabolism, and a reduction in Flourishing. Resources become idle, people are discouraged and deskilled, and the spacecraft won’t start anymore.

Nothing I have said so far should be surprising. And yet, in 2010 it was certainly the economic orthodoxy that Europe could revive its economic metabolism through a series of massive reductions in government spending across the Eurozone (the UK adopted a similar strategy).

Nevinomics sees this as a striking example of faulty system thinking. As a healthy individual who is stretched financially, I can certainly improve my situation by continuing to work as hard (or harder) – ensuring a continuation of income – and reducing expenditures. But, of course, improving my situation in this way requires others to continue to spend, since their spending is my income. 1)Both Canada and Sweden reduced government spending in the 1990s and ended up with much better economies. But they were lucky enough to have their crises when other economies were booming. The Clinton-era boom allowed Canada to come sailing out of its crises. As they say, timing is everything.

But if we all start reducing our spending, then there is a pretty predictable outcome – aggregate demand and output are reduced. And this is precisely what has happened in Europe for the PIIGS 2)PIIGS = Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain:

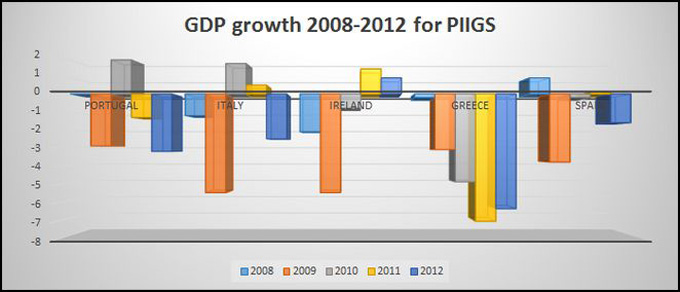

Figure 1: GDP growth 2008-2012 for PIIGS, year by year. 3)“GDP Growth.” The World Bank, 2013.

2009 was a particularly difficult year, as GDP declined in all PIIGS countries (close to 6% in Italy and Ireland) and has declined 5 straight years in Greece. This has obviously translated into massive increases in unemployment, particularly among young people.

Figure 2: Unemployment rate for PIIGS, Germany, France for 2007 and 2012. 4)“Unemployment Rate.” The World Bank, 2013.

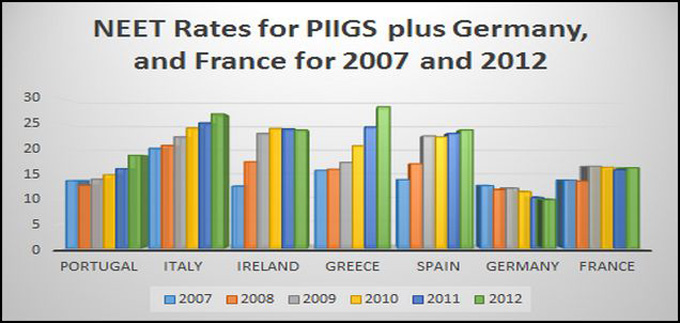

Figure 3: NEET rates. 5)“Young People Aged 18-24 Not in Employment and Not in Any Education and Training, by Sex and Nuts 2 Regions (from 2000 Onwards) – Neet Rates.” eurostat, 2013.

So, all in all, we have an unmitigated disaster measured both in terms of orthodox GDP and in terms of Flourishing, as a young person who is in NEET-status (“Not in Employment, Education or Training”) will have long-term challenges to achieve Flourishing.

Why would such a destructive idea – that universal austerity would put the UK and Europe back on the road to economic health – take hold?

At the core, Nevinomics believes this happens because orthodox economics conflates 2 separate concepts:

-

The economy has self-adjusting economic mechanisms – that is, economic actors adjust behaviour to circumstances.

-

The system effect of the totality of adjustments by economic actors will be an improvement in whatever metric we are pursuing (Flourishing in Nevinomics’ case, GDP in orthodox economics).

It is certainly true that individual actors in the economic ecosystem react to signals and conditions and change their behaviour – so 1 is correct. If my income declines and I am not sure it will recover, I spend less. But there is no a priori presumption 6)Well, there is this a priori assumption in orthodox economics, arising originally from Smith’s invisible hand and codified in mathematical proofs developed by Walras, Arrow, and Debreu among others. But In Nevinomics, nothing is taken for granted, and whether concept 2 is correct is an empirical question. that this mechanism will lead to better system outcomes – as Principle 1 of Nevinomics states, Economics is an empirical discipline, and whether and how the existing self-correcting mechanisms improve the economy is an empirical issue. So 2 is not necessarily true – it is an empirical question and needs to be studied.

In the aftermath of the GFC, this confusion in economic orthodoxy lead to the belief that if the government reduced spending, including reducing transfer payments, economic actors would re-balance to the private sector to restore high economic metabolism. But in the case of the severely depressed aggregate demand after the GFC, it is pretty obvious empirically that this was not the case.

And the damage goes beyond a short-term reduction in GDP while we wait for the economy to return to ‘normal.’ With massive shortfalls in aggregate demand, people are idled and there is a rapid deterioration in their skills, compounded by the psychological impact of long-term unemployment, and the well-documented habit of employers viewing the long-term unemployed as less desirable, so making the challenge of reintegration into the workforce even more difficult. People are just not like the spacecraft on The Planet of the Apes.

In fact, an interesting paper by DeLong 7)Brad DeLong was a friend during our PhD studies at Harvard and we team-taught an interesting sophomore course that covered Adam Smith, Marx, Durkheim, Weber, and Freud, among others. His blog is well worth reading. and Summers – 2 prominent representatives of the economic orthodoxy – makes precisely this point:

We are here to say that, as a matter of arithmetic, in a depressed economy like the present if a long deep recession casts even a small shadow on future potential output, with interest rates in the range at which the U.S. has been able to borrow, there is a substantial likelihood that expansionary fiscal policy right now would be self-financing, and an overwhelming likelihood that it would pass a benefit-cost test.

This as close to English 8)Here is where the argument starts to resemble English less and less: If higher output this year raises potential output in the future by a fraction η because it reduces the shadow cast by the downturn through discouraged workers, lost skills, broken organizations, and missing investment on future productivity, then boosting government purchases now, in an environment with a policy-relevant, net-of-monetary-policy-offset Keynesian multiplier μ, boosts future real GDP by the multiplier times some hysteresis coefficient η. That means that in an environment with a tax rate τ, the flow of future total tax collections are boosted by τημ. as they come; what this means is that if having people (and capital) unemployed implies that their future productivity is reduced, then the economy will be better off if you figure out how to put these resources to work in a more sensible way than having them sit idle. And you get them into use through fiscal stimulus, that is, government spending on things that will increase future productive capacity.

And it seems pretty likely that future productivity and output are reduced by enforced idleness. Principle 4 of Nevinomics – Realities about people – reminds us that we live through time. Casual observation tells us that if we are involuntarily unemployed, our skills and motivation will decline. I am not an expert, but I think it is likely a careful search of the literature will show this claim is backed up empirically: prima facie, the case is for fiscal stimulus, not universal austerity.

However, what I find most interesting about this article is that it was published in March 2012; during the period 2008-2011, a conclusion that would seem obvious to laypersons – that a large amount of unused human potential and productive capacity would harm future productive capacity (and Flourishing) – was not worthy of study by orthodox economics.9)Another example of understanding the economy in hindsight is Carmen and Rheinhart’s This time is different. They traced financial crises over 800 years and found not only that they are very common, but also that there are clear patterns prior to the crises. The book was published in 2009. Perhaps the world would have been a better place if it had been published in 2002. In fact, an intelligent layperson would likely have guessed that such an obviously important question would have been extensively studied and settled by economists long ago, a guess that would have been sadly mistaken.

While perhaps we can forgive DeLong and Summers for being late to think this through – in fact, they should be applauded for putting it on the agenda of mainstream economics – there can be no similar forgiveness for the IMF.10)J. Bradford Delong. and Lawrence H. Summers. “Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2012.1 (2012): 233-297. Project MUSE. Web. 1 Jan. 2014.

In October 2012, the IMF published a paper saying basically that it had severely underestimated the fiscal multiplier – the total effect of fiscal spending – because of course the recipients of the initial spending go out and spend, as well, and so on (my consumption is your income). 11)“Developments suggest that short-term fiscal multipliers may have been larger than expected at the time of fiscal planning… Research reported in previous issues of the WEO finds that fiscal multipliers have been close to 1 in a world in which many countries adjust together; the analysis here suggest that markers may recently have been larger than 1…” International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2012. Accessed on February 17, 2014. Fiscal Multipliers.

The impact, of course, of underestimating the fiscal multiplier is to underestimate the impact of fiscal contraction in the eurozone, basically prescribing austerity policies that produced much more economic and human misery than necessary. I will spare the reader the sanitized – and opaque – language 12)Page 41 of the report has the relevant analysis (Fiscal Multiplier). At a presentation to Governor Sanusi of the Central Bank of Nigeria (who won the award for top central banker in the world in 2010), the Governor and I had a spirited discussion that ended with him saying ‘You see, Andrew, basically all the successful economies in Asia have pretended to listen to the IMF, but done the opposite.’ Stiglitz – former Chief Economist of the IMF – wrote a scathing attack on the impact of IMF policies. It seems that in GFC, the IMF has not learned much. the IMF uses to describe this mistake.

The important point is simply that mainstream economists continue to make massive policy errors that impact people’s lives. And this analysis does not even consider the insights from DeLong and Summers – that when people and capacity are idled, the skills and energy of the economic ecosystem rapidly deteriorate, further compounding the challenges and impact on Flourishing.

When we step back, what is this debate about?

Fundamentally, Nevinomics believes it cannot be the right economic policy to leave significant resources in society idle, not from the traditional GDP perspective and certainly not from the Flourishing perspective.

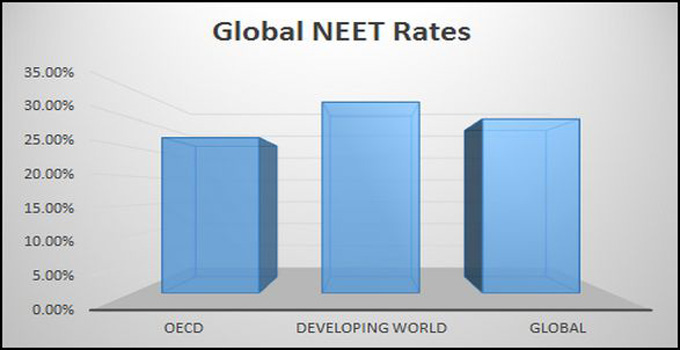

And yet, we have vast unused human resources in both the developed and less developed world (as shown in Figures 2 and 3, above). In the OECD countries, 26.6% young people (15-24) are NEET. 13)“Oecd Factbook 2013: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics.” OECD Publishing, NEET. In the developing world, this number is a staggering 32.7%. Altogether, globally, 29.8% of young people are NEET. 14)“The Challenge of Youth Unemployment.” World Economic Forum, Youth.

Figure 4: Global NEET Rates

So the system that starts young people on the path to Flourishing is broken.

How do we fix it? This will be the subject of many future Nevinomics articles, starting with The Labour Market – The Greatest Market Failure Ever, Part 1.

Footnotes

| 1. | ↑ | Both Canada and Sweden reduced government spending in the 1990s and ended up with much better economies. But they were lucky enough to have their crises when other economies were booming. The Clinton-era boom allowed Canada to come sailing out of its crises. As they say, timing is everything. |

| 2. | ↑ | PIIGS = Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain |

| 3. | ↑ | “GDP Growth.” The World Bank, 2013. |

| 4. | ↑ | “Unemployment Rate.” The World Bank, 2013. |

| 5. | ↑ | “Young People Aged 18-24 Not in Employment and Not in Any Education and Training, by Sex and Nuts 2 Regions (from 2000 Onwards) – Neet Rates.” eurostat, 2013. |

| 6. | ↑ | Well, there is this a priori assumption in orthodox economics, arising originally from Smith’s invisible hand and codified in mathematical proofs developed by Walras, Arrow, and Debreu among others. But In Nevinomics, nothing is taken for granted, and whether concept 2 is correct is an empirical question. |

| 7. | ↑ | Brad DeLong was a friend during our PhD studies at Harvard and we team-taught an interesting sophomore course that covered Adam Smith, Marx, Durkheim, Weber, and Freud, among others. His blog is well worth reading. |

| 8. | ↑ | Here is where the argument starts to resemble English less and less: If higher output this year raises potential output in the future by a fraction η because it reduces the shadow cast by the downturn through discouraged workers, lost skills, broken organizations, and missing investment on future productivity, then boosting government purchases now, in an environment with a policy-relevant, net-of-monetary-policy-offset Keynesian multiplier μ, boosts future real GDP by the multiplier times some hysteresis coefficient η. That means that in an environment with a tax rate τ, the flow of future total tax collections are boosted by τημ. |

| 9. | ↑ | Another example of understanding the economy in hindsight is Carmen and Rheinhart’s This time is different. They traced financial crises over 800 years and found not only that they are very common, but also that there are clear patterns prior to the crises. The book was published in 2009. Perhaps the world would have been a better place if it had been published in 2002. |

| 10. | ↑ | J. Bradford Delong. and Lawrence H. Summers. “Fiscal Policy in a Depressed Economy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2012.1 (2012): 233-297. Project MUSE. Web. 1 Jan. 2014. |

| 11. | ↑ | “Developments suggest that short-term fiscal multipliers may have been larger than expected at the time of fiscal planning… Research reported in previous issues of the WEO finds that fiscal multipliers have been close to 1 in a world in which many countries adjust together; the analysis here suggest that markers may recently have been larger than 1…” International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2012. Accessed on February 17, 2014. Fiscal Multipliers. |

| 12. | ↑ | Page 41 of the report has the relevant analysis (Fiscal Multiplier). At a presentation to Governor Sanusi of the Central Bank of Nigeria (who won the award for top central banker in the world in 2010), the Governor and I had a spirited discussion that ended with him saying ‘You see, Andrew, basically all the successful economies in Asia have pretended to listen to the IMF, but done the opposite.’ Stiglitz – former Chief Economist of the IMF – wrote a scathing attack on the impact of IMF policies. It seems that in GFC, the IMF has not learned much. |

| 13. | ↑ | “Oecd Factbook 2013: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics.” OECD Publishing, NEET. |

| 14. | ↑ | “The Challenge of Youth Unemployment.” World Economic Forum, Youth. |